What is it and how much do you need?

By John balboa

Dietary

protein…it’s one of the most important topics when it comes to your physique

and making improvements to it.

If you’ve

ever wondered what it is, why it’s so important, and how much you should be

eating, check out this article.

What are proteins?

Proteins are

organic molecules made up of amino acids – the building blocks of life. These

amino acids are joined together by chemical bonds and then folded in different

ways to create three-dimensional structures that are important to our body’s

functioning.

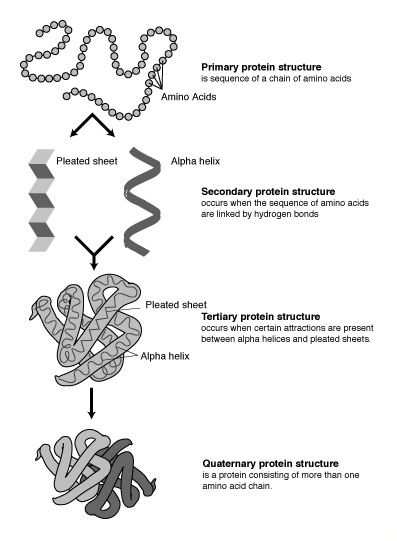

A diagram of

protein structures. For more reading on protein structure, check out Madison

Technical College’s Lab Manual on Protein Structure.

There are

two main categories of amino acids in the body. First, we’ve got essential

amino acids – those that the body can’t manufacture, and thus we must consume

in our diets.

Some amino

acids are conditionally essential, which means that our bodies can’t always

make as much as we need (for example, when we’re under stress).

Next, kinda

obviously, we’ve got nonessential amino acids – those that the body can usually

make for itself.

|

Essential

amino acids

|

Conditionally

essential amino acids

|

Nonessential

amino acids

|

|

|

|

Why is it important to get enough protein?

During

digestion, the body breaks down the protein we eat into individual amino acids,

which contribute to the plasma pool of amino acids. This pool is a storage

reserve of amino acids that circulate in the blood.

The amino

acid pool in the bloodstream readily trades with the amino acids and proteins

in our cells, provides a supply of amino acids as needed, and is continuously

replenished. (Think of it like a Vegas buffet of protein for the cells.)

Since our

bodies need proteins and amino acids to produce important molecules in our body

– like enzymes, hormones, neurotransmitters, and antibodies – without an

adequate protein intake, our bodies can’t function well at all.

Protein

helps replace worn out cells, transports various substances throughout the

body, and aids in growth and repair.

Consuming

protein can also increase levels of the hormone glucagon, and glucagon can help

to control body fat.1 Glucagon is released when blood sugar levels go down.

This causes the liver to break down stored glycogen into glucose for the body.

It can also

help to liberate free fatty acids from adipose tissue – another way to get fuel

for cells and make that bodyfat do something useful with itself instead of

hanging lazily around your midsection!

How much protein do you need?

How much

protein you need depends on a few factors, but one of the most important is

your activity level.

The basic

recommendation for protein intake is 0.8 grams per kilogram (or around 0.36 g per

pound) of body mass in untrained, generally healthy adults. For instance, a 150

lb (68 kg) person would consume around 54 grams a day.

However,

this amount is only to prevent protein deficiency. It’s not necessarily optimal,

particularly for people such as athletes who train regularly and hard.

For people

doing high intensity training, protein needs might go up to about 1.4-2.0 g/kg

(or around 0.64-0.9 g/lb) of body mass.2 Our hypothetical 150 lb (68 kg) person

would thus need about 95-135 g of protein per day.

These

suggested protein intakes are what’s necessary for basic protein synthesis (in

other words, the creation of new proteins from individual building blocks). The

most we need to consume throughout the day for protein synthesis probably isn’t

more than 1.4 – 2.0 g/kg.

But wait –

there’s more!

Beyond the

basics of preventing deficiency and ensuring a baseline of protein synthesis,

we may need even more protein in our diets for optimal functioning, including

good immune function, metabolism, satiety, weight management and performance.3

In other words, we need a small amount of protein to survive, but we need a lot

more to thrive.

We can only

store so much protein at one time. As the graph below shows, the body’s protein

stores fluctuate over the course of a day. Notice how the upper limit never

increases; the amount of protein in the body just cycles up and down as we eat

or fast.

Image

source: DJ Millward, The Metabolic Basis of Amino Acid Requirements.

The

take-home here is that you can’t simply eat a 16-pound steak (a la Homer

Simpson consuming “Sirloin A Lot”) once and be done with it. The body needs its

protein stores to be continually replenished, which means that you should

consume moderate amounts of protein at regular intervals – which just happens

to be an important Precision Nutrition guideline.

Consuming

more protein may help maintain an optimal body composition (in other words,

help you stay leaner and more muscular) and a strong immune system, good

athletic performance, and a healthy metabolism. It may promote satiety (i.e.

make you feel full longer) and consequently help you manage your body weight.

Indeed,

physique athletes such as bodybuilders have long relied on the rule of 1 gram

of protein per pound of body weight – or 150 g per day for a 150 lb individual.

For extra credit

When you eat

protein is just as important as how much. After resistance exercise (RE) such

as weight training, the body synthesizes proteins for up to 48 hours after

training.4

Interestingly,

during and immediately after RE, protein breakdown is increased as well. In

fact, for a brief period, the rate of breakdown exceeds the rate of building.

The body

actually drops into a short-term wasting or catabolic state. However, taking in

enough protein during the pre- and post-exercise period can offset catabolism.

(Check out the Precision

Nutrition guide for more on nutrition timing.)

The graph

below shows that as the blood concentration of essential amino acids (EAA)

increases, so too does protein synthesis.

Image

source: ABCBodybuilding.com

The graph

below shows how amino acid (and amino acid + carbohydrate) consumption after

exercise results in a positive muscle protein balance (in other words, helping

muscles rebuild, which is a good thing), while the intake of no nutrients can

result in a negative muscle protein balance.

Image

source: GSSI

Which

protein is best? In general it’s your choice – both protein from plant sources

and animal sources seem to work equally well in increasing muscle protein

synthesis as a result of exercise.5 The amino acid leucine seems to act as a

major stimulus for protein synthesis; good sources of leucine include

spirulina, soy protein, egg white, milk, fish, poultry, and meat.

Can I eat too much protein?

If you

overeat protein, this extra protein can be converted into sugar or fat in the

body. However, protein isn’t as easily or quickly converted as carbohydrates or

fat, because the thermic effect (the amount of energy require to digest,

absorb, transport and store protein) is a lot higher than that of carbohydrates

and fat.

While 30% of

the protein’s energy goes toward digestion, absorption, and assimilation, only

8% of carbohydrate’s energy and 3% of fat’s energy do the same.

You might

have heard the statement that a high protein intake harms the kidneys. This is

a myth. In healthy people, normal protein intakes pose little to no health

risk. Indeed, even a fairly high protein intake – up to 2.8 g/kg (1.2 g/lb) –

does not seem to impair kidney status and renal function in people with healthy

kidneys.6 In particular, plant proteins appear to be especially safe.7

Summary and recommendations

For basic

protein synthesis, you don’t need to consume more than 1.4 to 2.0 g/kg (around

0.64-0.9 g/lb) of protein per day.

Nevertheless,

consuming higher levels of protein (upwards of 1g per pound of body weight) may

help you feel satisfied after eating as well as maintain a healthy body

composition and good immune function.

You should

consume some protein before and after training to ensure adequate recovery.

Eat, move, and

live… better.

Yep, we

know… the health and fitness world can sometimes be a confusing place. But it

doesn’t have to be.

Let us help

you make sense of it all with this free special

report.

In it you’ll

learn the best eating, exercise, and lifestyle strategies — unique and

personal — for you.

Endnotes

1. Flatt JP

1978; Tappy L, 1996; Blom WA et al., 2006; Latner JD, Schwartz M, 1999.

- Lemon et al 1981; Tarnopolsky et al 1988; Tarnopolsky et al 1991.

- Flatt JP 1978; Tappy L, 1996; Blom WA et al., 2006; Latner JD, Layman et al 2003; Schwartz M, 1999; Tangney CC, et al. 2005; Kishino Y & Moriguchi S 1992; Marcos A, et al 2003.

- Dreyer et al 2006; Koopman et al 2006; Biolo et al 1995; Phillips et al 1997; Norton et al 2006; MacDougall et al 1995.

- Brown et al 2004; Anthony et al 2007; Kalman et al 2007.

- Poortmans JR & Dellalieux O 2000.

- Am Diet Assoc 2003; Millward DJ 1999.

Post A Comment:

0 comments: